Eulogy: “Millionaire” Phone-a-Friend

Guest writer Travis Eberle laments the loss of the legendary lifeline.

As Who Wants To Be A Millionaire: Hot Seat surpasses the 1,000-episode mark in its native Australia, and as the revamped American version of the show moves production to a new state and gains its second new host in eight months, guest writer Travis Eberle talks about another drastic change the show has made in its 15-year history.

It’s been five or six years since the Phone-a-Friend lifeline was unceremoniously and unpredictably taken away from Millionaire contestants. I’ve heard several reasons for it: the phone partner was frequently using a search engine to come up with the answers, it took too long to get the editing right, and others. I don’t care; I think it is a blow to a once-great program.

When the show made its debut here, the Phone-a-Friend helped to shake up what could be a run-of-the-mill quiz with an enormous top prize. Since each lifeline could only be used once, they had to be used judiciously. Asking the audience was usually first to be played if there was a low-level question about pop culture or recent events about which the contestant had no clue; the wisdom of groups played out repeatedly.

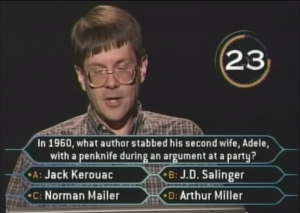

But then came the dilemma: do I really need some help or can I save the lifeline for later on? And once the decision is made, who do I call? After the call, do I trust my partner? Lots of times the partner said he or she was dead-to-rights confident of their answer, but the help ended up being wrong (Rudy Reber’s $500,000 question played out that way, along with other less famous examples.) If the partner gives an answer that doesn’t reinforce what you thought, do you jettison your old answer or stick to your principles? In the old days, before the clock, we got to see the contestant’s inner monologue.

Part of using the lifeline well was knowing how to parse a question such that you get the information to the partner without eating up too much time. Lots of contestants wasted time with greeting pleasantries and purple prose in the question that didn’t help, to their cost. Other contestants used their time to recite a list of search engine terms. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t.

At its heart any game show is an unscripted drama: who will win, how much, will someone dethrone the champion? Or, in a more macabre analogy: will the tightrope walker fall to his grisly death or make it to the other side? Phone-a-Friend ramped up the tension as both sides tried to do what they had to do while the thirty seconds frantically ticked away. Other times we got comedy, as evidenced by how the first winner used his phone call to place his stamp on quiz show history and (briefly) become a national celebrity.

Other than at the titular level of The $64,000 Question, I can’t recall an instance where someone was allowed and encouraged to seek outside help in this way. (Contestants who opted to try for the $64,000 jackpot were allowed to bring on an expert in the chosen specialist subject.) Note that several quiz shows have made use of it now, to varying degrees of success, as well as mockery. Twenty-One’s “second chance” was an obvious patch job, while the “classroom” of students on Are You Smarter Than A Fifth Grader? made a silly game a little more interesting.

So what did we get in return? Ask the Expert, a mixed blessing. Just like with the phone call the contestant got a brief Skype call with a previous winner, celebrity or noted brain. At least with Phone-a-Friend you were allowed to choose who to call; with the Expert, you got whoever the show picked. If you were lucky you got Ken Jennings, Pat Kiernan or an astrophysicist. If you were unlucky you got a bubble-headed newsreader or New York Times crossword compiler Will Shortz. Some performed better than others but it was a far cry from the usefulness of the phone call.

One of the reasons given for the elimination of the lifeline was that contestants were having their partner use a search engine to come up with the answer. To which I say, “so what?” The Australian version of the show was able to solve that issue by sequestering the partners and going live to their soundproof room when the time came. The usefulness of the phone call is inverse to that of asking the audience: the farther a contestant goes in the game the better it is. If a contestant can make it to $500,000 and is able to divine the answer because the question Googles well, is that so bad? I don’t think so. The show has only had five winners at that level so I don’t buy that so much as a reason. You could make the case that it took too long to edit around the phone call, but I thought the people working at Millionaire were professionals.

In the long run, is this so terrible? Of course not, it’s just a game show. But I watch Millionaire these days and see a very different game. Whether the game is better or worse is up for debate (I think the “shuffle round” would be an interesting competitive exercise), but with each new tweak or rule we get away from something that was truly special: a game that anyone could play or play-along with, a game that had excitement, strategy, tension and fun, and a game that changed the television landscape for better or worse.

Travis Eberle wrote for the BBC quiz Only Connect for five series. He lives in Kent, Washington and is studying to complete a certification in accounting and finance.